Q&A with Bill Adair on "Beyond The Big Lie"

Bill would like to apologize to C-SPAN caller Brian from Michigan, thinks Meta avoids fact-checking politicians out of self-interest, and is still disappointed in his former neighbor Mike Pence.

Hello and welcome to this special edition of Faked Up.

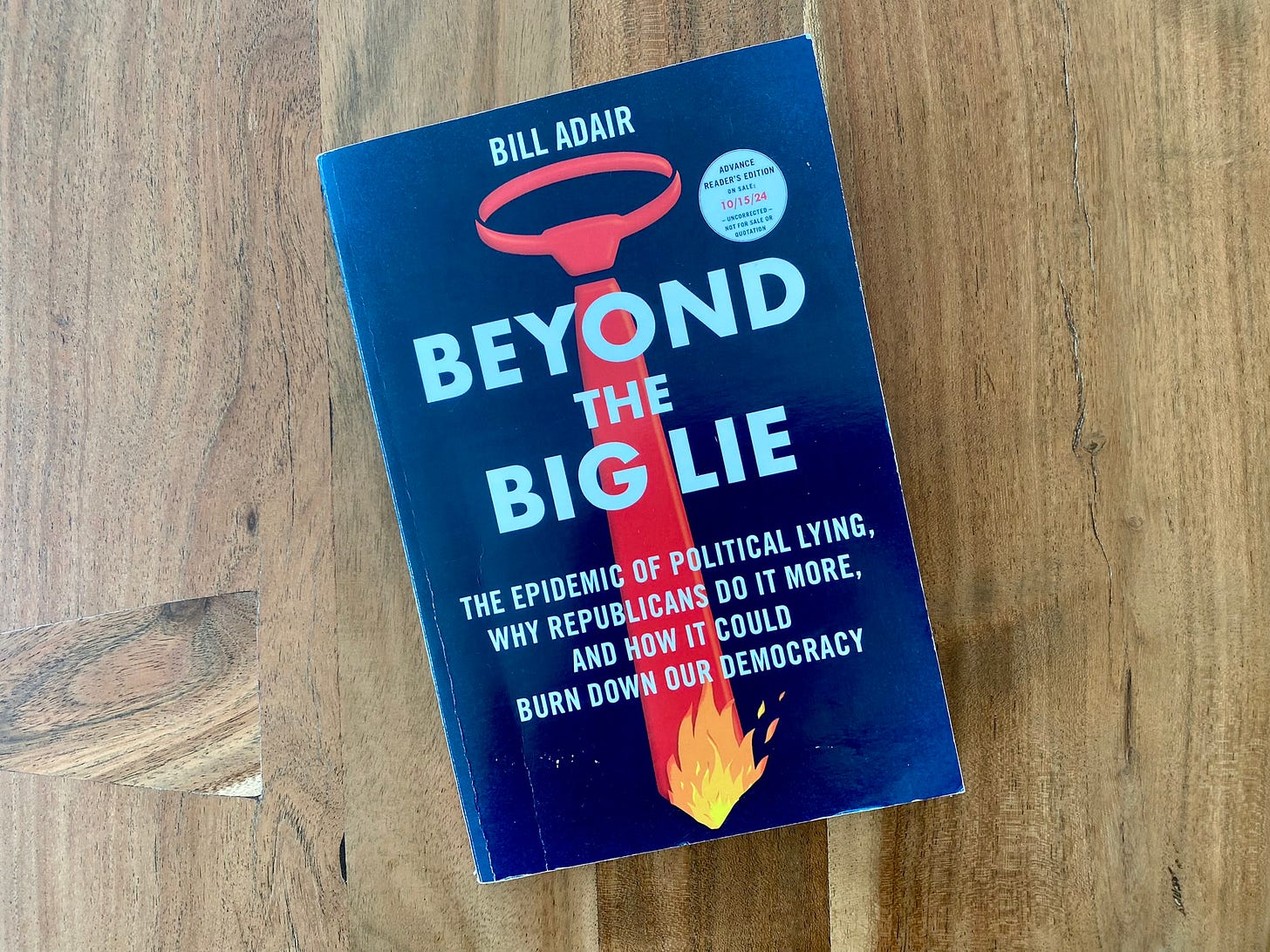

This is a Q&A with my friend and mentor Bill Adair about his new book “Beyond the Big Lie” which is out today.

Bill is a professor of practice of Journalism and Public Policy at Duke and the founder of Pulitzer-prize winning fact-checking website PolitiFact. Bill inspired me and many others around th…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faked Up to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.