What’s up, readers?

Faked Up #8 is brought to you by the largest moon in the solar system and my new corrections policy. The newsletter is a ~7-minute read and contains 55 links.

Update: Last week I wrote that “AI Steve,” an avatar for a British dude running for the British parliamentary seat of Brighton Pavilion was likely running on GPT-3. OpenAI did not reply to my email, but it did tell CNN two days later that it has taken down AI Steve’s account. The avatar still claim it runs on “chat GPT,” fwiw.

Top Stories

AUTO GLOB

404 Media’s Emanuel Maiberg committed to the bit and commissioned an AI-generated content farm. For just $365.63 and two days work, a Fiverr freelancer used the ChatGPT API to reword 404 Media articles and a plugin to auto-publish them on a WordPress site (see also FU#6, and the screenshot below).

Maiberg’s piece shows that we can hold two things to be true at the same time: (i) generative AI has made it easier than ever to “monetize filling the internet with garbage” and (ii) auto blogs will never replace true news outlets.

COPYCOP SHIFTS

Cybersecurity firm Recorded Future claims that CopyCop, a likely Russian-affiliated influence network, has launched 120 new domains and shifted its attention to the U.S. election. The operation, similar but separate from Doppelganger, “likely scrape[s] articles from legitimate news organizations to plagiarize them using generative AI” then adapts them to exacerbate political tensions.

A few things that stood out to me:

CopyCop is likely tied to John Mark Dougan.

It takes the network ~24 hours to convert a source post into the final product (I thought they would be able to do this faster?)

One way Recorded Future has been able to detect coordination across the network has been through reused images that preserved their highly specific file names.1

The network “has seen little to no amplification on social media” for now.

CopyCop used generative AI to create 1,041 inauthentic journalist profiles with uninventive biographies like the ones below. The cookie cutter nature of the operation extended to the point that most new websites had exactly ten journalists each.

MADE BY I

Two weeks ago, I noted that Instagram and Threads were the only platforms rolling out labels on AI-generated images as promised. (Watermarking is also in the White House’s voluntary commitments that Meta and others signed.)

Now, TechCrunch reports that the social networks may be over-labeling images as synthetic. For instance, this genuine 40-year-old picture by photographer Pete Souza.

Petapixel found that merely removing a tiny spot from a genuine image with Photoshop’s Generative Fill was enough to trigger the label — even as other AI-powered Adobe features did not.

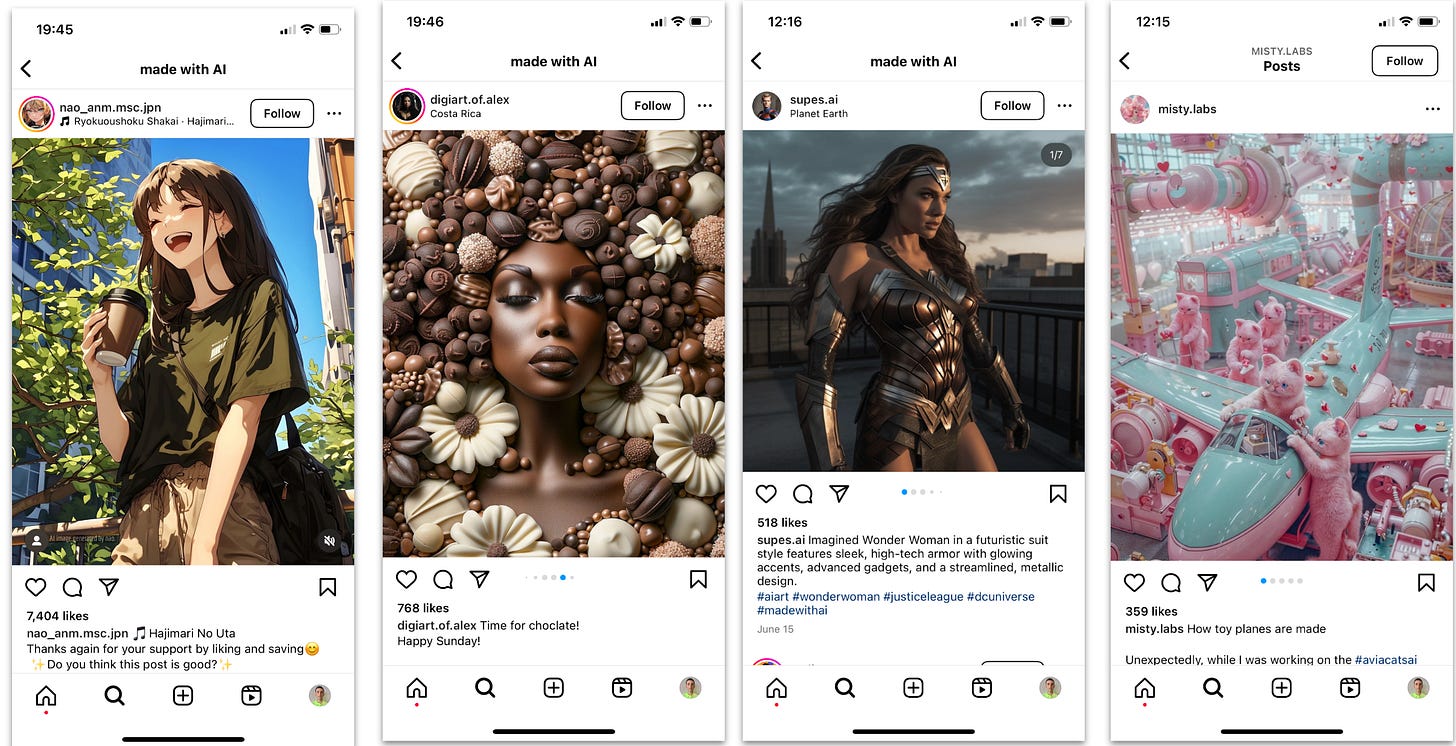

When I searched for [Made by AI] on Insta, I found a variety of pictures like the ones below that were clearly entirely AI-generated but unlabeled. That’s because they were likely created with tools that haven’t signed on to C2PA, like Stable Diffusion.

On Threads, the situation was similarly hit-and-miss. One user who claims to have “the technical abilities of a teaspoon” got an innocuous leaflet labeled. On the other hand, my upload of a screenshot of four WhatsApp AI stickers and an image reportedly created on Firefly and went unlabeled. (Let’s not even get into the rainbow hallucination at the bottom left of my request for “a pizza.”)

So to recap: labels triggered when they shouldn’t have. They triggered for minimal edits that will likely confuse users and not serve the purpose of helping detect deceptive edits. And they did not trigger at all for some fully AI-generated content.

Instagram head Adam Mosseri had this to say in a recent interview:

“I want to be super clear: There will be content on all platforms that is made by AI and is not marked as AI because that platform was not able to detect it because the person who made it specifically tried to avoid it.”

Remember that when anyone claims labeling is a solution to AI-generated disinfo.

ONE MORE BILL

Last week, a group of U.S. senators led by Ted Cruz and Amy Klobuchar introduced the TAKE IT DOWN Act. This is, by my count, the fifth bill in front of Congress that would regulate deepfake nudes. The others are the Preventing Deepfakes of Intimate Images Act, the DEEPFAKES Accountability Act, the DEFIANCE Act and the NO AI FRAUD Act.

Generally speaking, the bills would all enable victims of synthetic nonconsensual intimate imagery (NCII) to pursue civil or criminal charges against the disseminator of the content. TAKE IT DOWN also introduces an obligation on platforms to remove deepfakes flagged by a victim within 48 hours from being notified.

Even in the hyperpolarized context of 2024 America, these provisions are supported by bipartisan coalitions in Congress and a vast majority of the public. No one, it seems, is in favor of technologically-assisted sexual harassment. What is more, multiple states allow civil or criminal prosecution of deepfake nudes of adults.

So what’s holding back a federal ban? Quite possibly, the U.S. Constitution, according to legal scholar Ben Sobel.

In an upcoming paper, Sobel notes that the very real harm these bills want to mitigate doesn’t quite fit within existing jurisprudence on privacy or defamation. Instead of exposing privately-held true facts, deepfake nudes “confabulate non-factual expression” from “readily available” public photographs. Deepfake nudes are also usually not shared or consumed as real: A big “false” label would on most occasions not obviate their opprobrium.

Sobel argues that this leaves deepfake legislation within the territory of outrageous expression. The constitutionality of bans in this broad category has been litigated in cases around flag-burning, effigy-desecration and virtual child sexual abuse material (CSAM). Attempts to punish outrageous expression have on occasion run in trouble in courts, as with U.S. v Valle, where a police officer who communicated about torture fetishes online alongside photos and names of real women was ultimately acquitted.

Still, bans on outrageous expression appear in American law today, in the statutes that prohibit trademark dilution by “tarnishment" and “morphed” CSAM2. If these measures are constitutional, Sobel says, perhaps deepfake legislation is as well.

I asked Sobel whether any of the federal laws, if approved, looks most resistant to free speech challenges. His full response is worth reading in its entirety here. Essentially, he thinks there are three elements whose treatment “probably correlate positively” with the laws being upheld as constitutional: deception, dissemination and documented harms.

All else being equal, bills that focus on banning dissemination (rather than creation) and documented harms such as sexual harassment (rather than the fake qua fake) should fare better.

This leaves the question of deception: “It’s uncontroversial that the law can prohibit fraudulent or defamatory speech without running afoul of the First Amendment,” Sobel says. But as we’ve seen, that is not really the issue with deepfake nudes. As Sobel summarizes it in his paper:

“Regulating non-deceptive deepfakes is not about deciding what private facts may be disclosed, or what lies may be told, or what abuse may be recorded […] It is about deciding how our society will tolerate its members to be depicted.”

Ultimately, I subscribe to the argument made by moral philosopher Carl Öhman in the “Pervert’s Dilemma” that deepfake nudes are not fantasies but “a technically-supported systemic degrading of women.” So my tolerance is pretty low!

But I also came out of researching this snippet legitimately worried that U.S. courts might push back against a deepfake nudes law3. Which translates into a call to action for all of us who care about this harm to promote an all-of-society response that includes education, platform moderation and public norm-setting in addition to smartly-crafted legislation.

THE UN ENTERED THE CHAT — The United Nations launched on Monday a set of Global Principles for Information Integrity. They don’t cover much new ground tbh, but the calls to action are a good snapshot of the minimum common denominator at the intergovernmental level. For instance, the UN calls on tech platforms to “allocate sufficient and sustained dedicated in-house trust and safety resources and expertise that are proportionate to risk levels” (love it) and to “clearly label” AI-generated content (good luck). They even have recommendations for fact-checking, who are encouraged to “adhere to standards of independence, non-partisanship and transparency” (sounds familiar).

LLMS CORRECTING LLMS

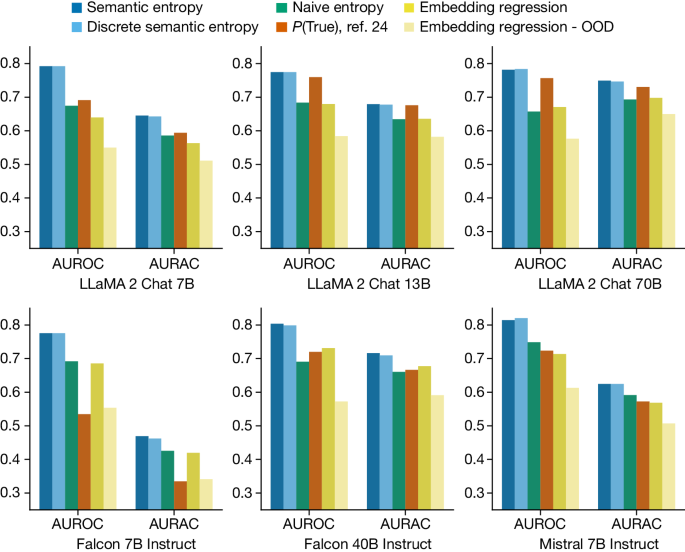

On Nature, computer scientists at the University of Oxford presented the results of their effort to detect LLM hallucinations with LLMs (see also WaPo write-up). In a skeptical riposte, RMIT computer scientist Karin Verspoor warns that this approach could backfire “by layering multiple systems that are prone to hallucinations and unpredictable errors.”

If I understand the figure below correctly, the accuracy of this method, billed “semantic entropy,” is still only about 80%.

Headlines

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faked Up to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.